Po tylu miesiącach kwarantanny, a tym samym zamknięcia MET, w końcu dostaliśmy zielone światło na odwiedziny tego magicznego miejsca. Ponieważ ponowne otwarcie brzmi jak świętowanie, wraz z moją najnowszą torebkę 3,1 Phillip Lim pobiegłam do MET ze łzami w oczach. Muszę przyznać, że to największe muzeum w kraju stało się dla mnie drugim domem. Niestety, przy wciąż trwających ograniczeniach związanych z pandemią, kolejne zamknięcie MET stoi pzed znakiem zapytania, więc postanowiłam wymyślić plan, który umożliwi mi dokumentacje moich ulubionych kolekcji na dłuższą chwilę. W związku z tym poprosiłam 10-ciu nieznajomych, aby zrobili mi 10 zdjęć przed moimi ukochanymi dziełami sztuki, na wypadek kolejnego lockdown (lepiej dmuchać na zimne). Pozwól więc, że zabiorę Cię na wirtualną wycieczkę po MET i pokażę Ci najbardziej niesamowite obrazy i rzeźby, które znajdują się w stałej kolekcji the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

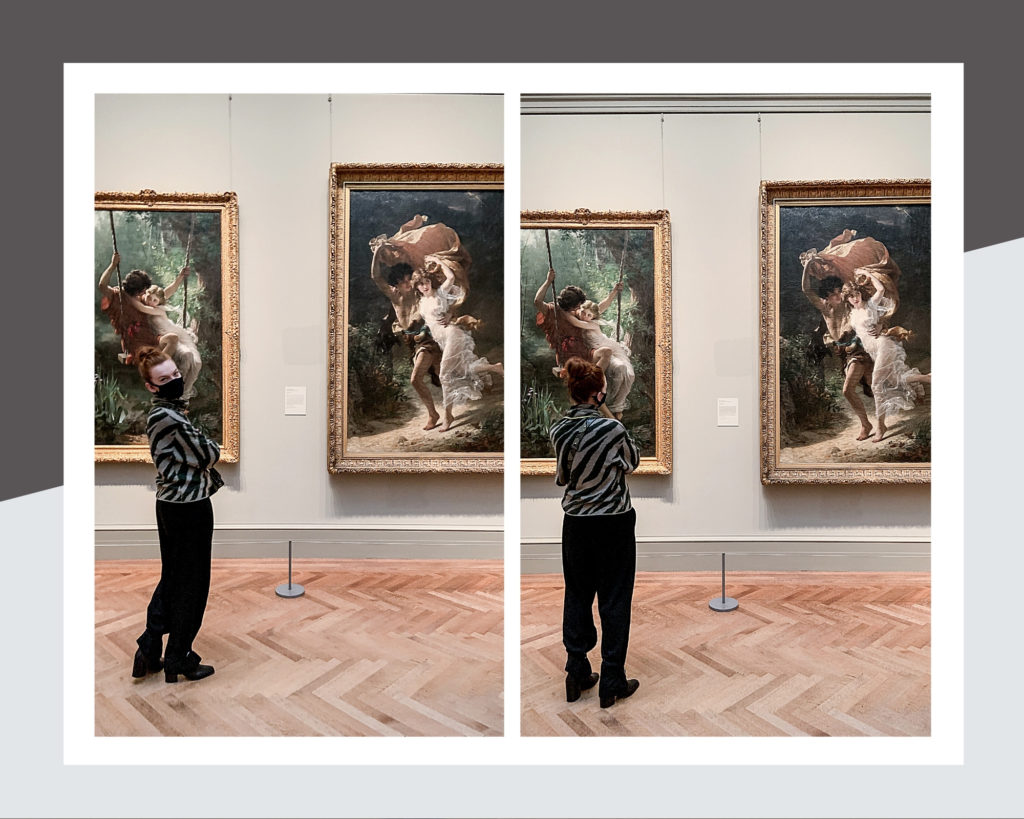

1. Springtime (1873) and The Storm (1880), Pierre-Auguste Cot

This flirtatious duo in classicizing dress, painted with notable technical finesse, reflects Cot’s allegiance to the academic style of his teachers, including Bouguereau and Cabanel. Exhibited at the Salon of 1873, the picture was Cot’s greatest success, widely admired and copied in engravings, fans, porcelains, and tapestries. Its first owner, hardware tycoon John Wolfe, awarded the work a prime spot in his Manhattan mansion, where visitors delighted in „this reveling pair of children, drunken with first love … this Arcadian idyll, peppered with French spice.” Wolfe’s cousin, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, later commissioned a similar scene from Cot, The Storm

When Cot exhibited this painting at the Salon of 1880, critics speculated about the source of the subject. Some proposed the French novel Paul and Virginie by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737–1814), in which the teenage protagonists run for shelter in a rainstorm, using the heroine’s overskirt as an impromptu umbrella; others suggested the romance Daphnis and Chloe by the ancient Greek writer Longus. New York collector and Metropolitan Museum benefactor Catharine Lorillard Wolfe commissioned the work under the guidance of her cousin John Wolfe, one of Cot’s principal patrons. Like the artist’s earlier Springtime (2012.575), it was immensely popular and extensively reproduced.

2. Diana (1893-94), Augustus Saint-Gaudens

From its lofty perch on Madison Square Garden’s tower, the resplendent gilded Diana enjoyed iconic status on the New York City skyline from 1892 to 1925. Saint-Gaudens capitalized on its fame by issuing three variant reductions; in this second version, the lithe goddess, about to release her arrow, is poised atop a full orb on a two-tiered base. The lustrous patina was achieved by electro-plating a mixture of gold, copper, and zinc to the bronze surface.

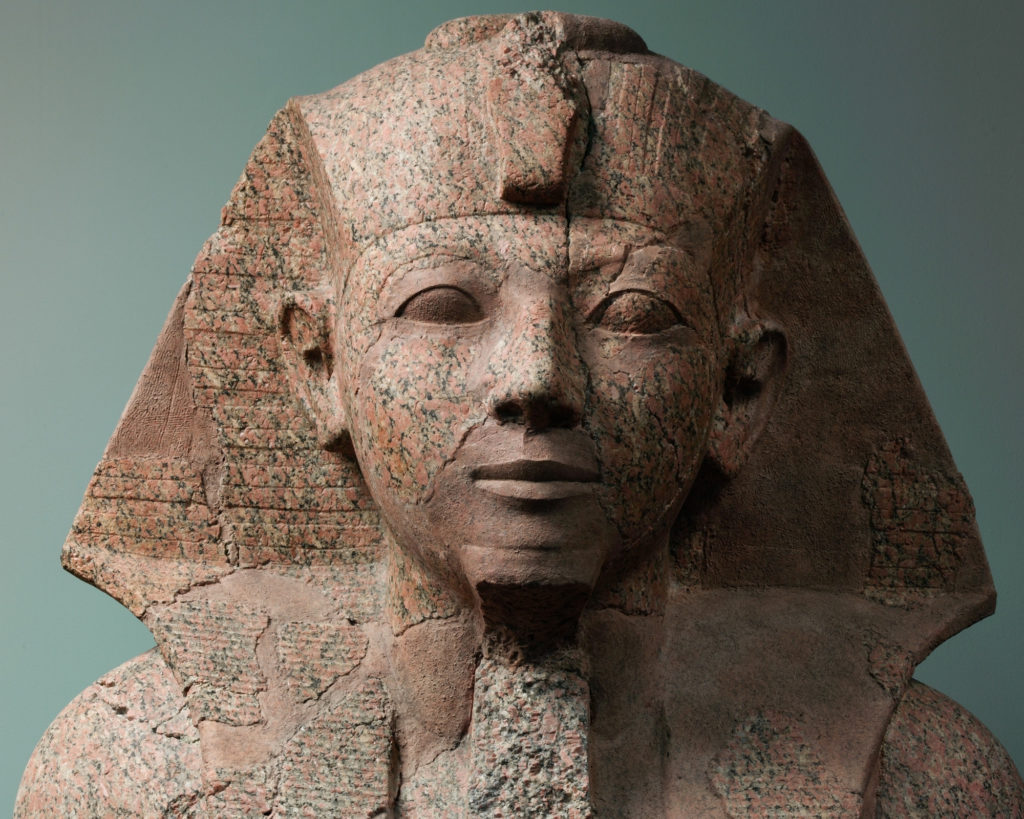

3. Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut

(ca 1479–1458 B.C.)

This over life-size kneeling statue and two others in the collection were made to flank the processional pathway along the axis of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. They depict Hatshepsut as the ideal Egyptian king – a young man in the prime of life. Each statue has an inscription that includes her personal name, Hatshepsut (literally foremost of noblewomen) and/or a feminine pronoun or verb form, so the masculine garb and physique were not intended to trick people into thinking that she was a man.

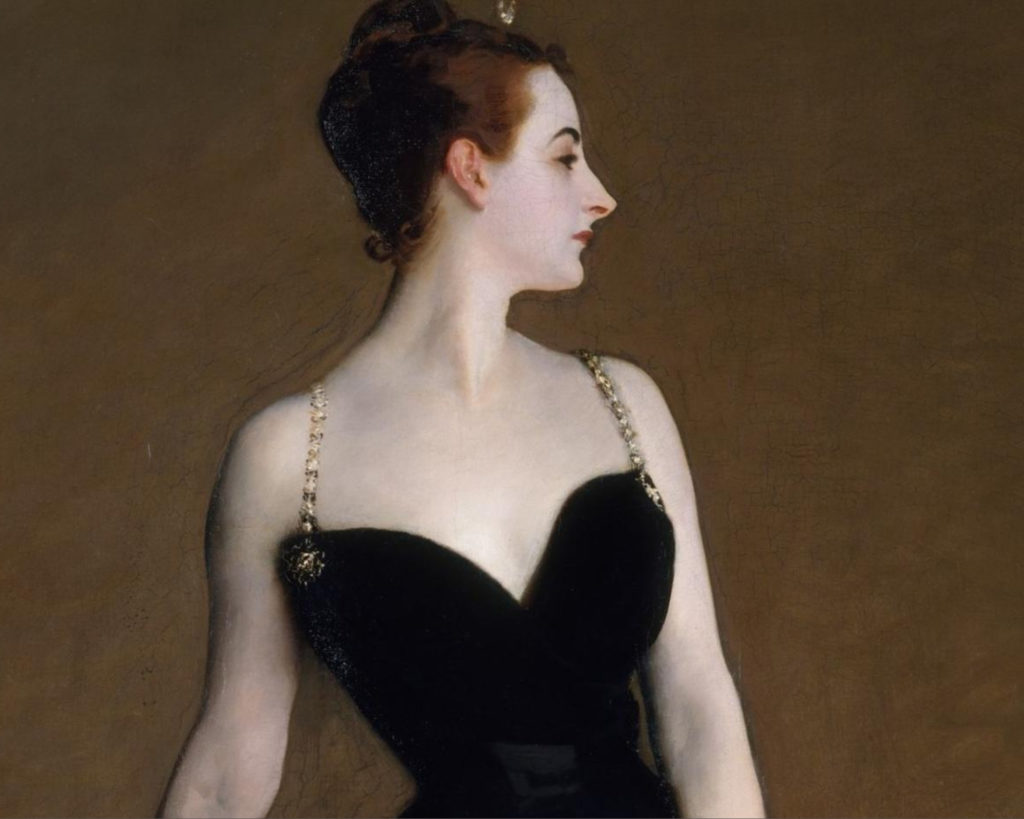

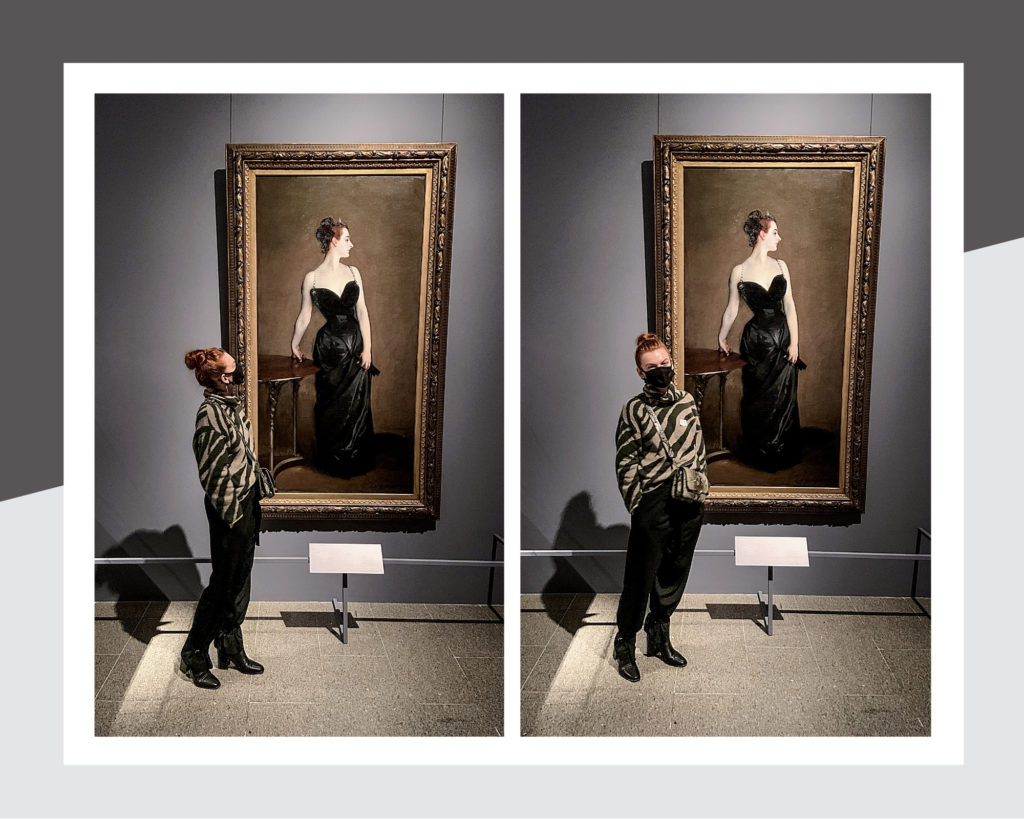

4. Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) (1883–84), John Singer Sargent

Madame Pierre Gautreau (the Louisiana-born Virginie Amélie Avegno; 1859–1915) was known in Paris for her artful appearance. Sargent hoped to enhance his reputation by painting and exhibiting her portrait. Working without a commission but with his sitter’s complicity, he emphasized her daring personal style, showing the right strap of her gown slipping from her shoulder. At the Salon of 1884, the portrait received more ridicule than praise. Sargent repainted the shoulder strap and kept the work for over thirty years. When, eventually, he sold it to the Metropolitan, he commented, “I suppose it is the best thing I have done,” but asked that the Museum disguise the sitter’s name.

5. Carousel State (1968), Sam Gilliam

Liberated from its stretcher, straddling the wall, and extending into space, Carousel State explores the material and chromatic possibilities of a traditional painting support. Gilliam developed his unique art-making approach in the 1960s while working within the milieu of the Washington Color School, a group of artists whose colorful compositions emphasized the flatness of the picture plane. This is an early example of the artist’s signature „drape paintings,” made through a novel process of dripping, smearing, staining, and splashing paint onto the raw canvas. Colors often spread and merged as Gilliam pressed and folded the fabric. He has described this almost as an act of equilibrium when, „the liquidity of the colors is reinforced by the fluidity of the canvas.” The final step in the creation of Carousel State is realized in its suspended installation, as it balances between the ceiling, wall, and floor.

6. The Temple of Dendur (completed by 10 B.C.)

Egyptian temples were not simply houses for a cult image but also represented, in their design and decoration, a variety of religious and mythological concepts. One important symbolic aspect was based on the understanding of the temple as an image of the natural world as the Egyptians knew it. Lining the temple base are carvings of papyrus and lotus plants that seem to grow from water, symbolized by figures of the Nile god Hapy. The two columns on the porch rise toward the sky like tall bundles of papyrus stalks with lotus blossoms bound with them. Above the gate and temple entrance are images of the sun disk flanked by the outspread wings of Horus, the sky god. The sky is also represented by the vultures, wings outspread, that appear on the ceiling of the entrance porch.

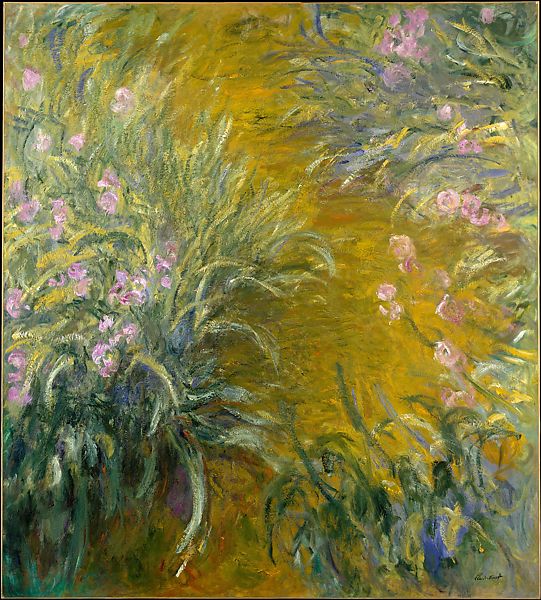

7. The Path through the Irises (1914–17), Claude Monet

Irises, among Monet’s favorite flowers, lined the pathways leading up to the house and Japanese bridge on the artist’s property at Giverny. This bird’s-eye view of a garden path belongs to a series of monumental works painted during the First World War that capture the vital essence of these flowers with intensity and breadth of vision. Late in life, as his eyesight faltered, he dispensed with subtlety and „took in the motif in large masses,” waiting „until the idea took shape, until the arrangement and composition inscribed themselves on the brain.”

8. A bronze statue of Artemis and a deer (1st century BC – 1st century AD)

The statue depicts Artemis, the Greek goddess of hunting and wildanimals amongst other things. She stands on a simple plinth in a pose that suggests she has just released an arrow from her bow. At some point in its history, the bow was separated from the sculpture and was lost. The goddess’s hair is wavy and parted, gathered at the back in a chignon. She wears a short chiton that folds at the waist and billows outwards and is partly covered by a himation. On her feet are laced sandals, and a stag stands alongside her. It is thought that the original sculpture may have included a jumping dog to the right of the goddess

9. Marble funerary lekythosca (375–350 B.C.)

The monument was presumably erected in memory of the young long-haired girl who clasps her father’s hand while her seated mother presents a bird to her little sister.

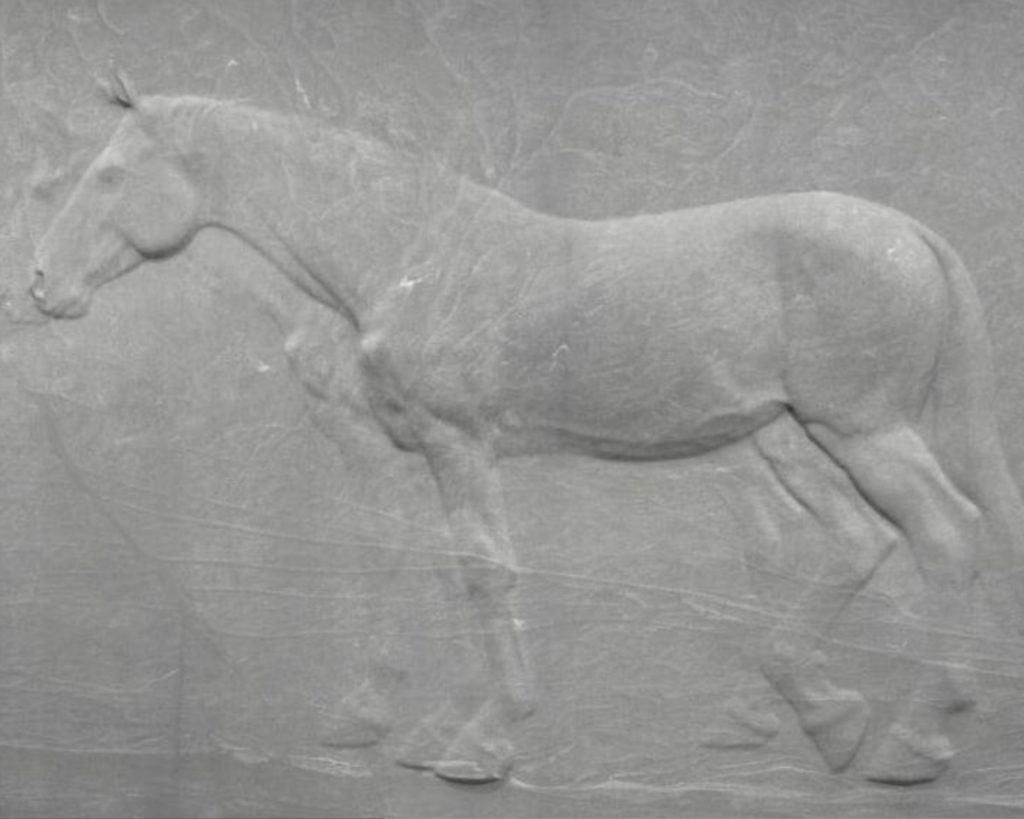

10. Two Horses (2019), Charles Ray

This monumental relief of Two Horses is the first work made by Ray in granite. Ray’s art reveals an acute understanding of the intertwined relationship between time and sculpture. For this wall relief he specifically chose a single block of Virginia granite—an igneous rock that evidences the slow process of geological petrification in its inherent striations. The mottled grey stone creates a surface that pulsates with a sense of movement, infusing the equine figures with a liveliness as the image appears and recedes from sight. Modeled on a single horse, the figure is doubled, with the rear animal seeming spectral and only partially visible. Time also manifests in this relief through Ray’s drawing upon a range of works in the history of art from funerary Greek stelae to the reliefs of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and from the painted horses on Attic vases, to equestrian sculpture from the Renaissance.