Welcome to the British Museum, a treasure trove of knowledge and culture nestled in the heart of London. Step into this magnificent institution and embark on a captivating journey through time and space. With its impressive collection and vibrant atmosphere, the British Museum offers an unforgettable experience for both history enthusiasts and curious visitors alike. Here are the most iconic art pieces everyone should see visiting the British Museum.

Hoa Hakananai’a

This statue, known as Hoa Hakananai’a, comes from the ceremonial village of Orongo on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). It is one of a number of statues, known as moai, for which the island is famous, which date to around AD 1000–1200.

Most moai were positioned on platforms (known as ahu), which generally faced away from the ocean, so the statues gazed inwards to the land and its people. Across Polynesia, Islanders worshipped ancestors who traced their lineages back to the gods. Moai were raised in honour of important deified ancestors. Today, Moai are described as the aringa ora, the living faces of the ancestors.

Hoa Hakananai’a is carved from hard basalt and on his back are a number of petroglyphs depicting frigate bird heads and human/bird figures, amongst other things. These relate to the island’s ‘birdman’ ceremonies which were associated with fertility and access to resources.

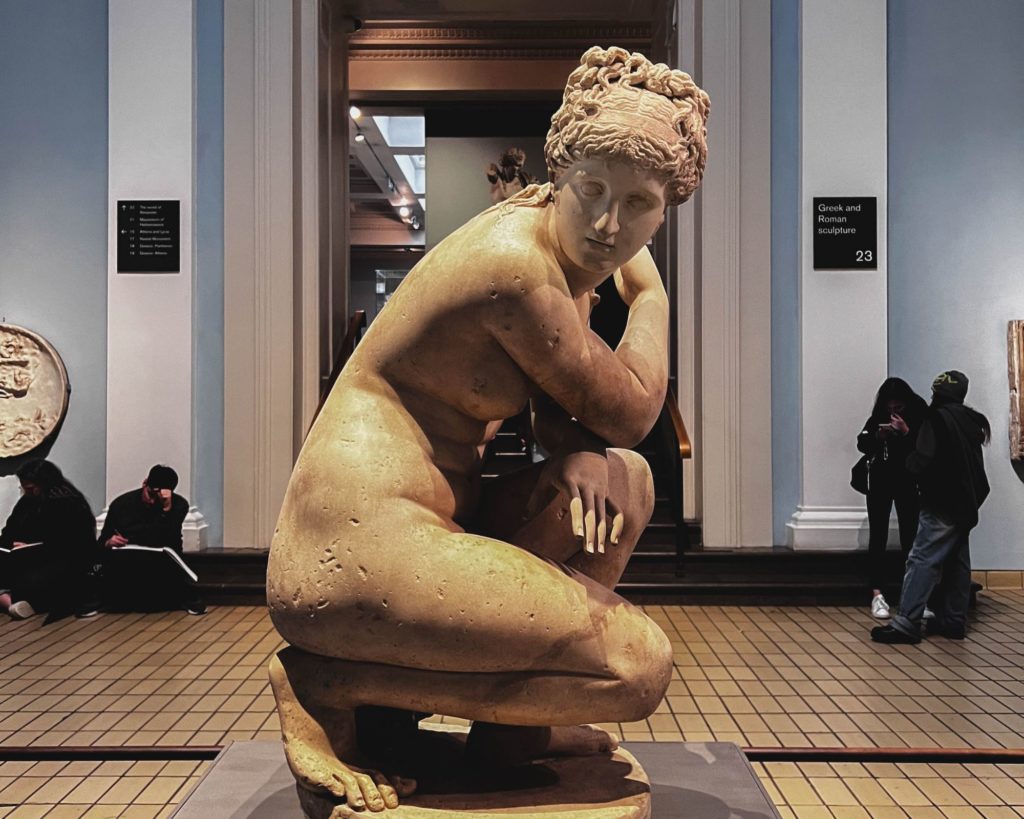

Crouching Venus

This sculpture, from the second century AD, is a Roman version of a much earlier Greek statue of the goddess Aphrodite, or Venus to the Romans. The Greek marble or bronze original, now lost, was perhaps made between 200 and 100 BC. Aphrodite was the Greek goddess of love and is often shown accompanied by Eros, the god of love, or cupids and doves. Here the sculpture makes the viewer a voyeur, surprising the goddess as she bathes.

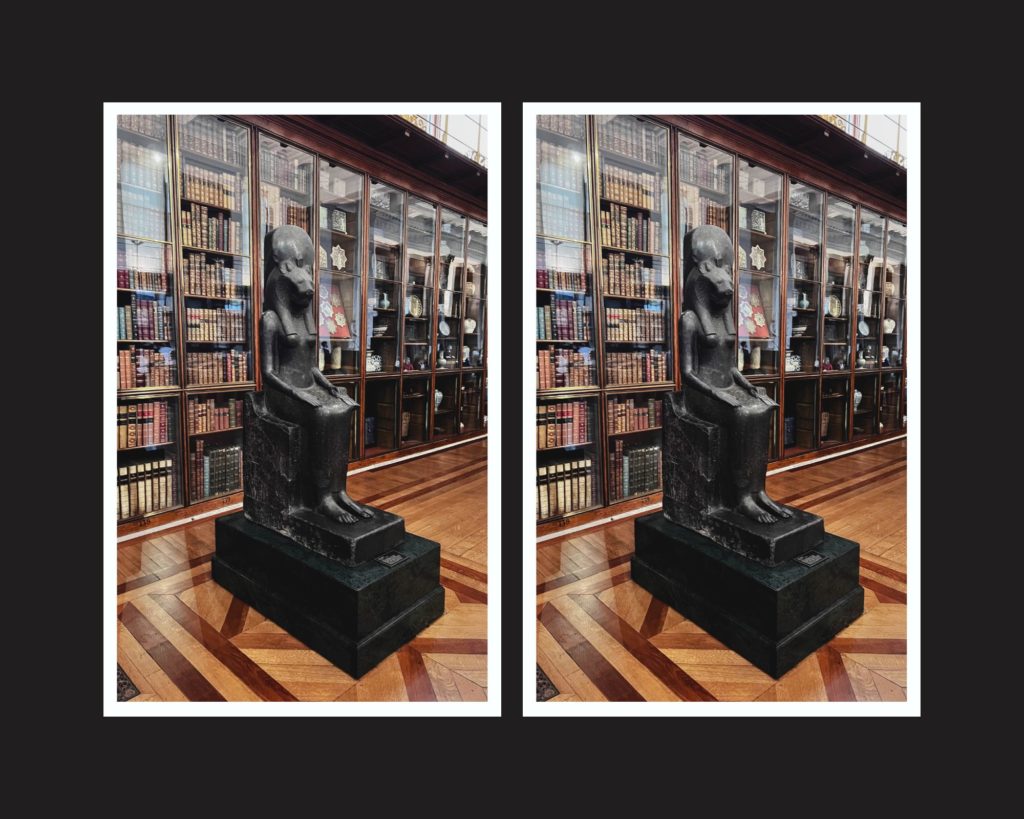

Bust of Ramesses the Great

This colossal bust is of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II, who reigned from 1279–1213 BC. Weighing an incredible 7.5 tonnes, the bust was once part of a larger statue which sat in the Ramesseum, a temple in Thebes (modern Luxor) built by the pharaoh. Its decoration celebrated his military achievements and his close association with the creator god Amun-Ra. The press coverage of the bust’s transportation to the UK is believed to have inspired the poet Shelley’s favourite sonnet, Ozymandias.

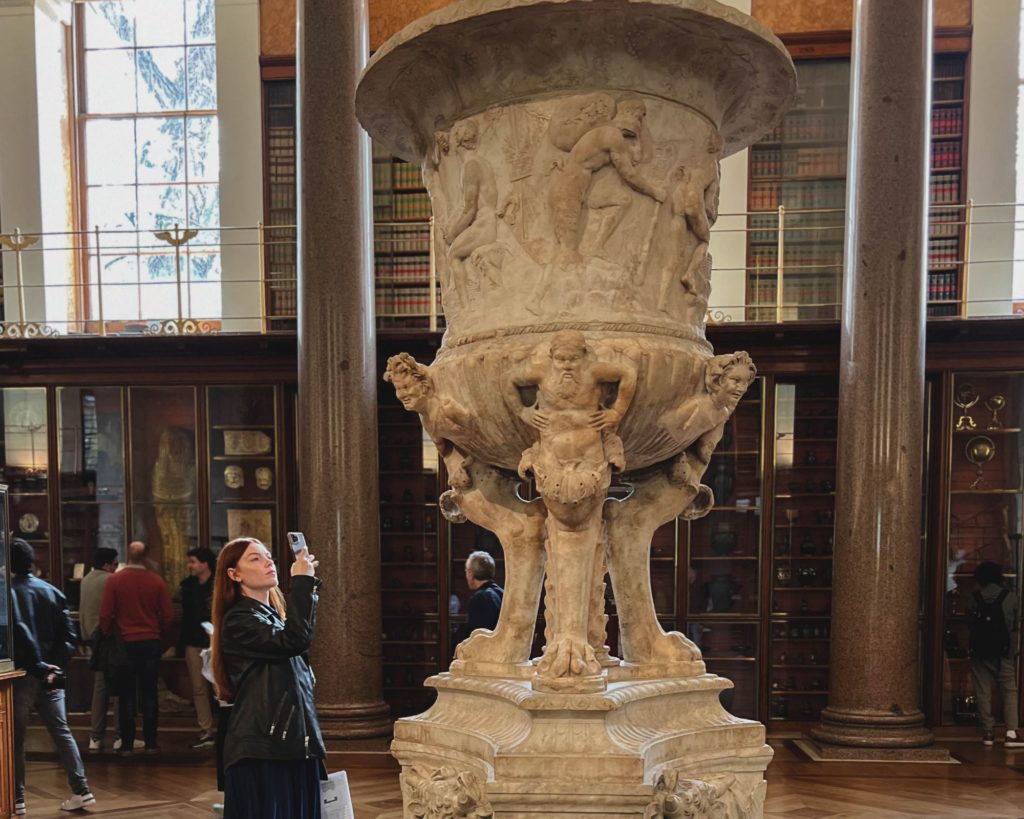

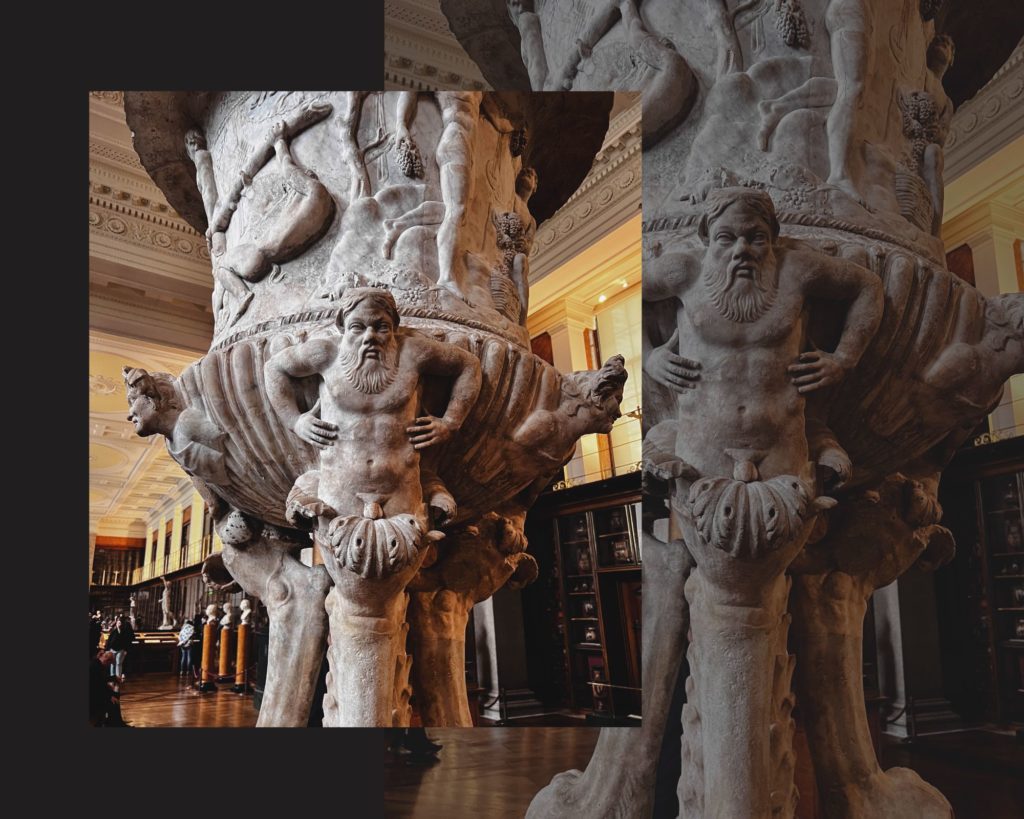

The Piranesi Vase

This 2.7-metre tall vase was constructed in the 1700s from a great number of classical fragments and modern additions. It belonged to the Italian engraver, architect and antiquarian Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1729–1778), who is best known for his architectural views of ancient and modern Rome, both real and imagined.

The vase, along with other pieces, was crafted by Piranasi from ancient fragments reportedly found at the Pantanello, a site on the grounds of the villa of the Roman emperor Hadrian at Tivoli, near Rome. He restored these fragments and incorporated them into highly decorative pastiches.

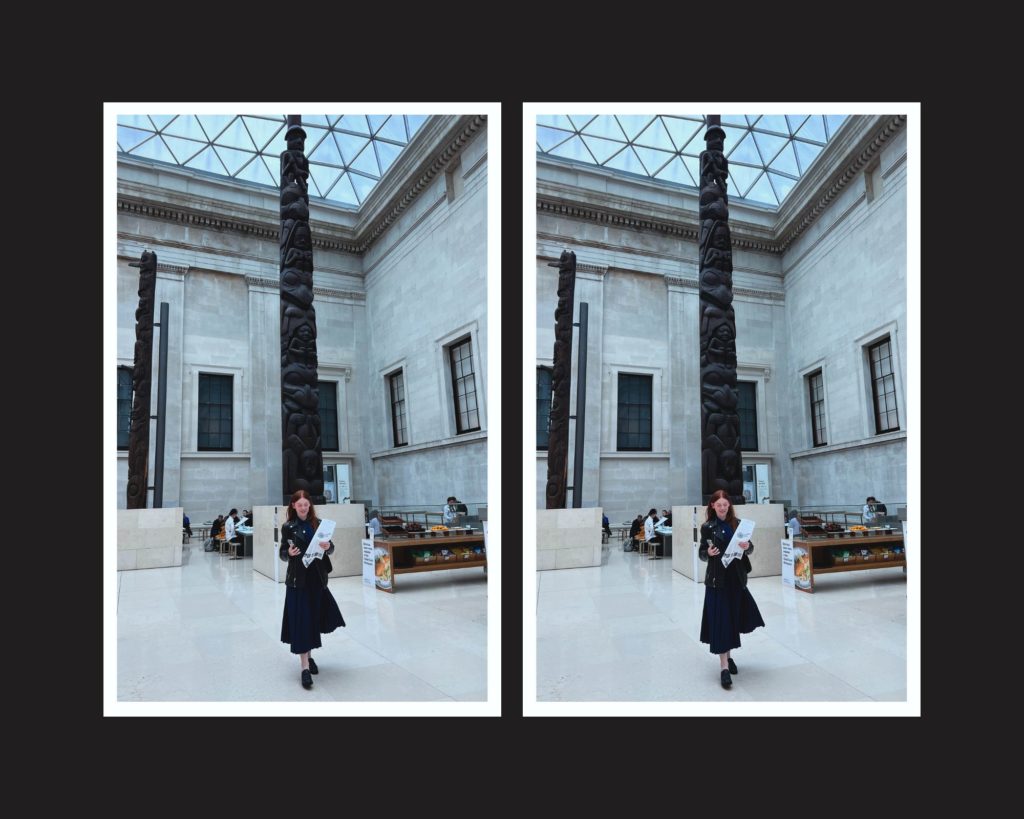

Haida House Pole

This pole was made around 1850 and once stood at the front of a clan house in the village of Kayang, British Columbia, Canada. It features crests – ancestral beings that mark identity and endow families with rights to stories and property. The House and village of Kayang was deserted due to epidemics introduced by Europeans in the 19th century. Chief of the House sold the pole to a doctor who then sold it to the British Museum.

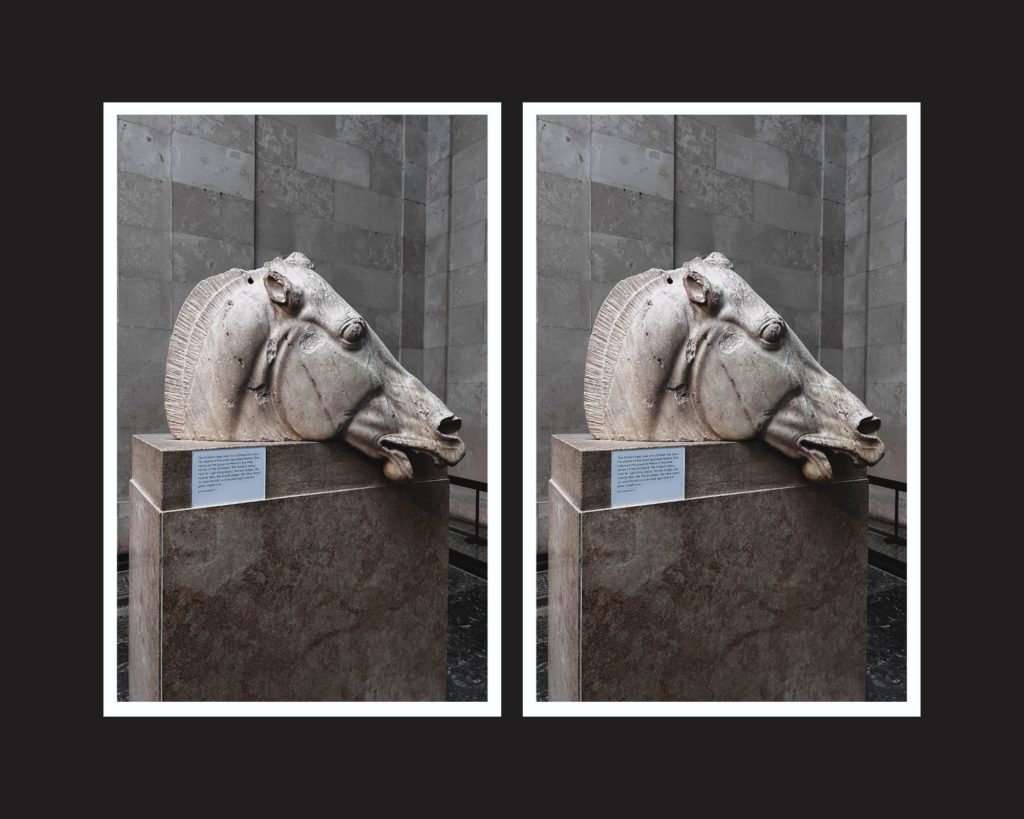

The Parthenon Sculptures

Carved about 2,500 years ago, these ancient Greek sculptures adorned the Parthenon, a temple on the Athenian Acropolis (the ancient citadel on a rocky hill in the city). The temple was dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthénos, who was the patron deity of Athens. The word parthénos means ‘maiden, girl’ or ‘virgin, unmarried woman’.

The temple was richly decorated with sculptures, designed by the artist Pheidias. The pediments (the triangular structure on the top of the temple) and metopes (carved panels) illustrate episodes from Greek myth, while the frieze represents the people of Athens in a religious procession to celebrate the birthday of the goddess. A colossal image of Athena made of gold and ivory once stood inside the temple – it is now lost.

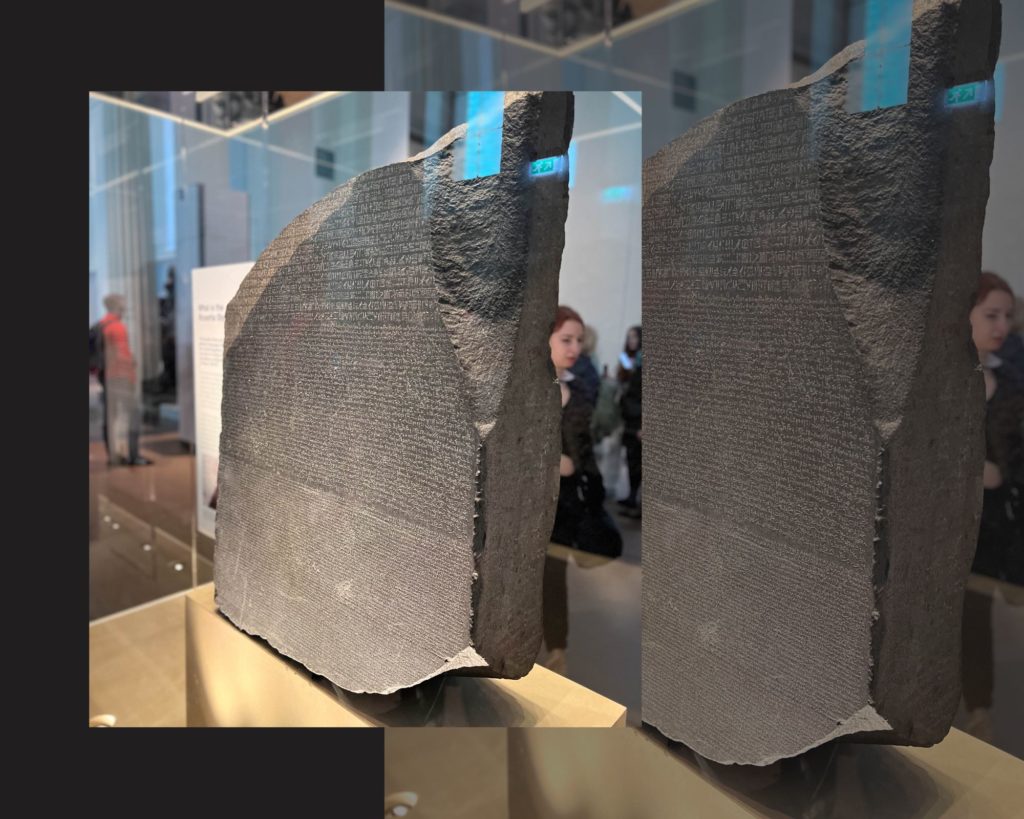

Rosetta Stone

The key that unlocked ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Rosetta Stone is one of the Museum’s most famous objects.

Once part of a larger stone slab, it is inscribed with a decree (official order) carved into it. The decree in itself is not particularly unusual, but as is written in three types of writing (or scripts) – hieroglyphs, Demotic (the native Egyptian script used for daily purposes, meaning ‘language of the people’) and Ancient Greek, meant that experts could use it to finally decipher hieroglyphics. This unlocked the world of ancient Egypt, from understanding its ancient history to beliefs in the afterlife

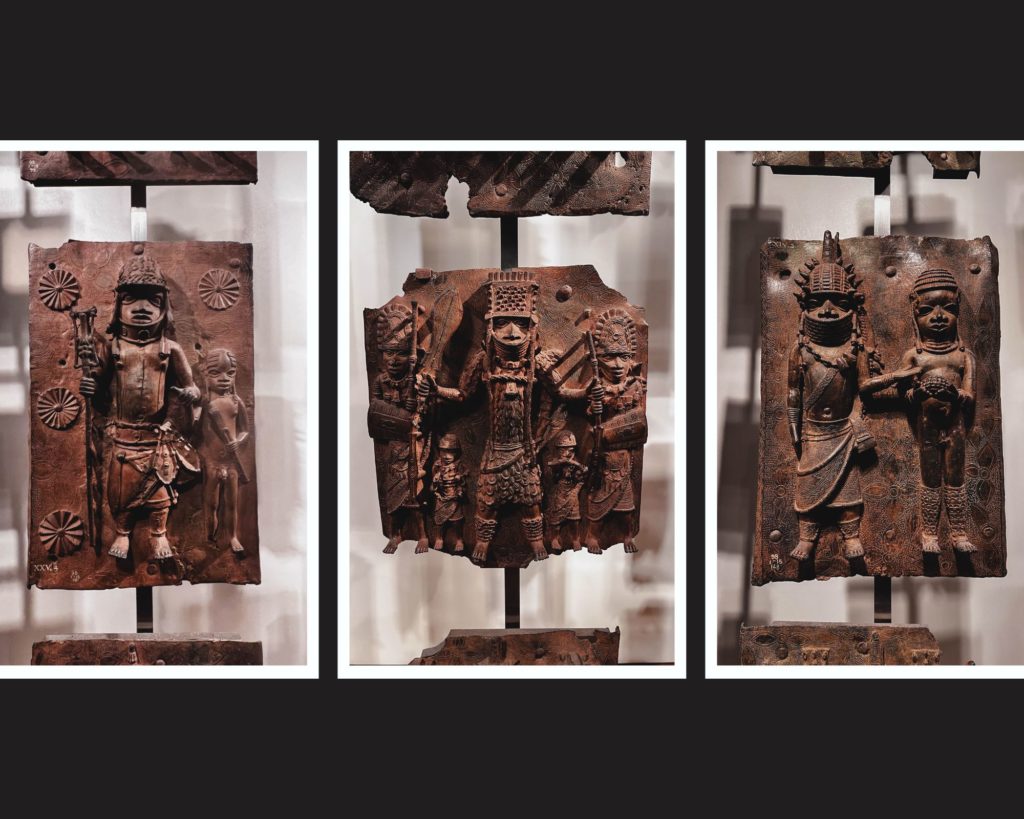

56 Benin bronze plaques

The ‘Benin Bronzes’ (made of brass and bronze) are a group of sculptures which include elaborately decorated cast plaques, commemorative heads, animal and human figures, items of royal regalia, and personal ornaments. They were created from at least the 16th century onwards in the West African Kingdom of Benin, by specialist guilds working for the royal court of the Oba (king) in Benin City. The Kingdom also supported guilds working in other materials such as ivory, leather, coral and wood, and the term ‘Benin Bronzes’ is sometimes used to refer to historic objects produced using these other materials.

Many pieces were commissioned specifically for the ancestral altars of past Obas and Queen Mothers. They were also used in other rituals to honour the ancestors and to validate the accession of a new Oba. Among the most well-known of the Benin Bronzes are the cast brass plaques which once decorated the Benin royal palace and which provide an important historical record of the Kingdom of Benin. This includes dynastic history, as well as social history, and insights into its relationships with neighbouring kingdoms, states and societies. The Benin Bronzes are preceded by earlier West African cast brass traditions, dating back into the medieval period.

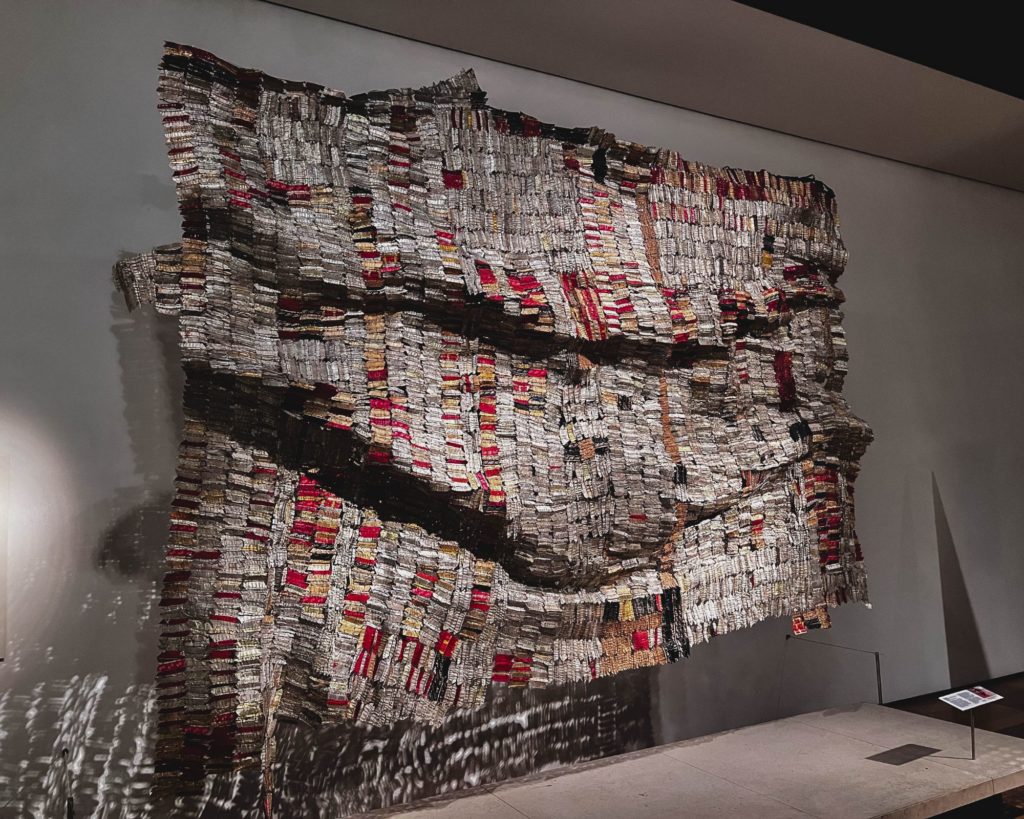

El Anatsui

One of the leading contemporary African artists, El Anatsui plays on the notion of combining the traditional and stereotypical with the unexpected and unusual. His work carries important cultural references and connotations. This cloth can be interpreted as a metaphor for both the fragile nature and the strength of tradition. Its structure mimicks that of a Kente cloth (narrow-strip woven silk cloth of Ghana) but the unusual recycled materials have been chosen to convey an underlying message of the negativity of consumerism.

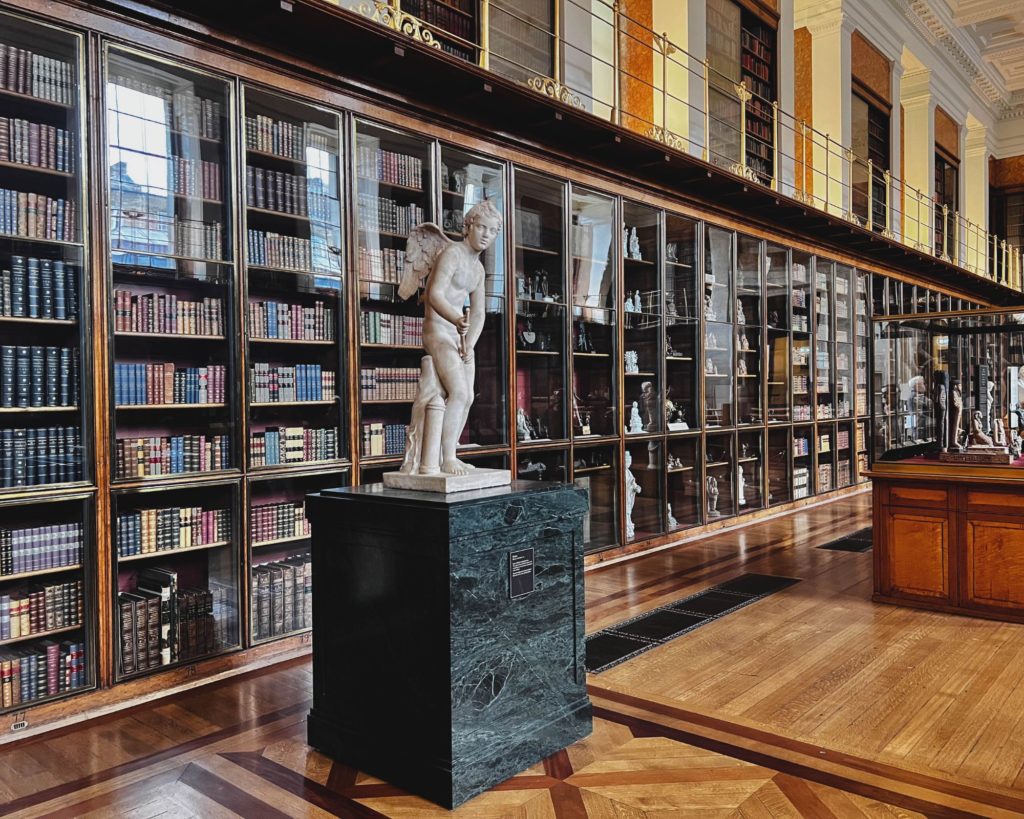

Enlightenment

Housed in the oldest room in the present Museum – originally designed to house King George III’s Library – this diverse permanent exhibition shows how British people understood the world at this time through their collections. The displays convey a sense of how objects were organised and displayed during the 18th century. Sir Hans Sloane’s collection, with several additional libraries and collections, became the foundation of the British Museum, which was established on 7 June 1753 by an Act of Parliament.

Housed in the oldest room in the present Museum – originally designed to house King George III’s Library – this diverse permanent exhibition shows how British people understood the world at this time through their collections. The displays convey a sense of how objects were organised and displayed during the 18th century. Sir Hans Sloane’s collection, with several additional libraries and collections, became the foundation of the British Museum, which was established on 7 June 1753 by an Act of Parliament.